When reliability matters more than performance

Context

In early-stage development, performance metrics often dominate discussions. Conversion rates, efficiencies, and peak outputs are easy to measure and useful for proving feasibility.

As technologies move toward industrial use, however, a different set of questions emerges. What matters most is not how a system performs under ideal conditions, but how it behaves when conditions vary, components age, and people have to operate it day after day.

From performance to dependability

In laboratory environments, performance is often optimised in isolation. Variables are controlled, experiments are short, and manual intervention is acceptable.

In industrial contexts, these assumptions no longer hold. Systems must tolerate variation in inputs, withstand extended operation, and recover predictably from disturbances. Under these conditions, reliability becomes a primary design objective.

This shift does not mean performance is unimportant. It means that peak performance without dependability rarely translates into a viable product.

Where reliability starts to dominate

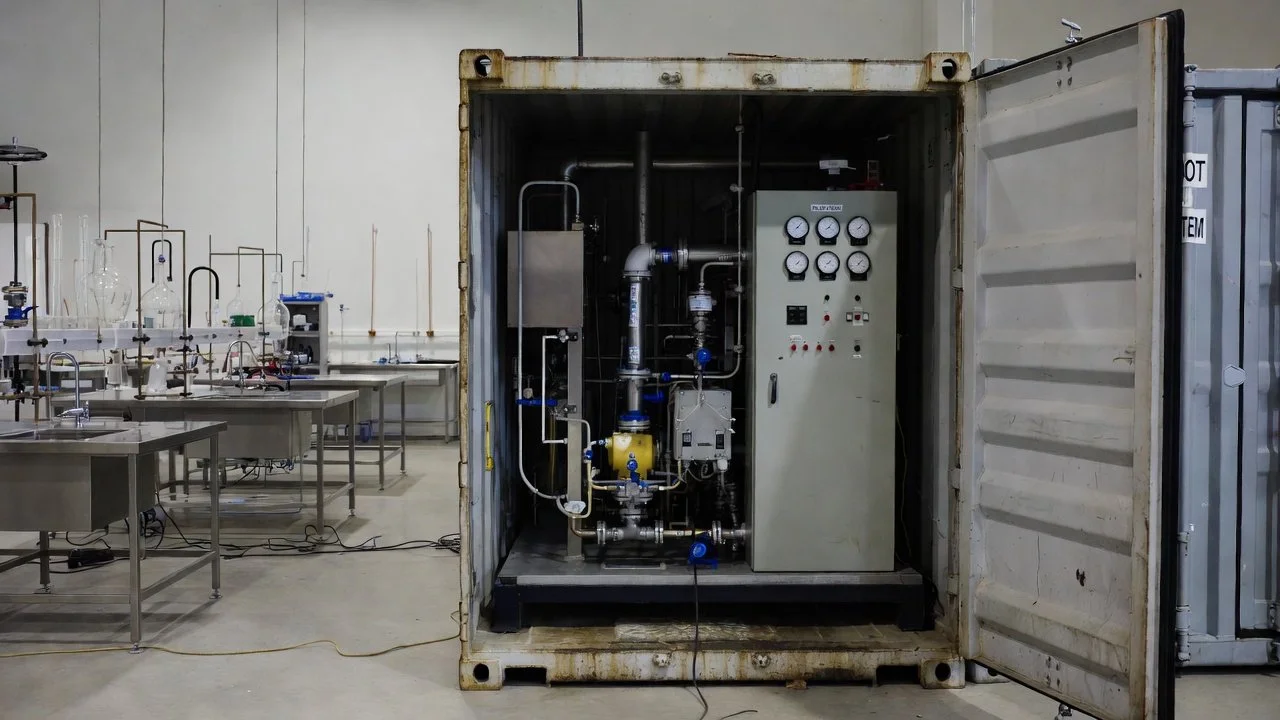

In our experience, the transition toward reliability-driven engineering typically coincides with pilot-scale development. Several factors contribute to this:

Extended operation exposes wear mechanisms and failure modes that short tests do not reveal.

Integration of auxiliary systems introduces new dependencies and interactions.

Operation by others highlights the need for clear interfaces, stable control, and predictable behaviour.

Compliance and safety requirements constrain component selection and operating envelopes.

At this stage, designs that perform exceptionally well in controlled tests may struggle to operate consistently in practice.

Engineering judgement under constraints

Designing for reliability requires a different mindset than optimising for performance. It involves making trade-offs that are not always visible in early metrics.

Examples include:

Accepting slightly lower efficiency in exchange for wider operating margins

Selecting components based on availability and robustness rather than nominal specifications

Prioritising maintainability and access over compact layouts

These decisions are rarely obvious from simulations or lab results alone. They emerge when engineering judgement is applied in the context of real operating constraints.

Collaboration between researchers and engineers

As reliability becomes a concern, engineering typically moves from a supporting role to a parallel discipline alongside research.

Researchers continue to refine the core technology, while engineers focus on how the system is built, operated, monitored, and maintained. This collaboration helps ensure that promising concepts are not constrained by assumptions that only hold at lab scale.

Bringing these perspectives together early reduces the risk of discovering fundamental limitations late in development.

Commercial and regulatory reality

At this stage, expectations also begin to shift. Clients are no longer asking whether a concept can work, but whether it can realistically become a product.

Reliability plays a central role in this assessment. Systems that require constant attention, specialised intervention, or narrowly defined operating conditions are difficult to certify, manufacture, and support.

Designing with reliability in mind helps align technical development with compliance pathways and commercial feasibility, without locking in a final product too early.

Closing perspective

Performance proves what is possible. Reliability determines what is usable.

As technologies move toward industrial reality, engineering success increasingly depends on recognising when optimisation must give way to dependability. Making that shift deliberately is key to turning promising concepts into systems that can operate safely, predictably, and at scale.